Articles, book chapters, and related media resources. For Tehrangeles Dreaming, see the Book page.

I have assembled a collection of audio-visual materials for each publication, including videos, images, screen grabs, cartoons, and more. See the media resources link at the end of each publication’s abstract.

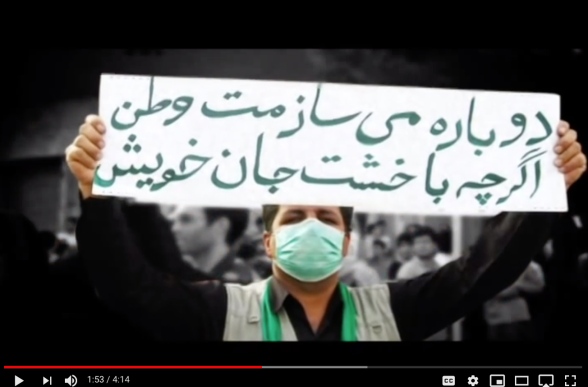

An Iranian protestor in 2009 holding a sign with the opening lines of Simin Behbahani’s poem “I Will Rebuild You, Homeland.” Screen grab from Dariush’s 2009 video “Khun bāzi” (Mainlining Blood / Playing with Blood)

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2017d. “Rebuilding the Homeland in Poetry and Song: Simin Behbahani, Dariush Eghbali, and the Making of a Transnational Anthem.” Popular Communication 15 (3):192-206.

Abstract: This article traces the transformation of an Iranian nationalist poem by Simin Behbahani (1981) entitled “I Will Rebuild You, Homeland” [دوباره می سازمت وطن / Dobāreh misāzamet vatan] into an expatriate national anthem, and the poem-song’s subsequent incorporation into protests and political speeches by individuals and groups in and outside of Iran. Employing musical and textual analysis, interviews, and a transnational perspective on cultural circulation and reception, I show how exile pop singer Dariush Eghbali’s adaptation of the original poem mobilized the text and opened it to audience participation. The article argues that the poem and its musical–textual permutations exemplify contemporary Iranian practices of national identification in which conflicting parties attempt to motivate “the Iranian people” to political ends. As actors from around the world and across the political spectrum repeatedly turn to nationalist poetry, song, anthem, and political speech, we observe how mass-mediated popular culture reveals ongoing recourse to nationalist forms even in transnational space.

Media Resources for “Rebuilding the Homeland in Poetry and Song”

Ermia performs on Googoosh Music Academy (Image Source)

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2017c. ““One Can Veil and Be a Singer!”: Performing Piety on an Iranian Talent Competition.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 13 (3):416-437.

Abstract: This article explores the media controversy surrounding the victory of Ermia, a veiled female vocalist, on the 2013 expatriate Iranian talent competition Googoosh Music Academy (GMA). A historically and ethnographically informed “ethnotextual” analysis of a selection of Persian-language television programs, articles and news reports, weblogs, and Facebook posts responding to Ermia reveals how a reality television contestant came to disturb simplistic but powerful binaries of modest/immodest, religious/secular, Iranian/Western, and national/diasporic as she combined signifying elements of these positions into one unsettling figure. The article shows how Ermia’s case gathered political valence through the contentious transnational Iranian mediascape and the televised talent genre’s premise—representing “real,” “ordinary” contestants and fostering audience participation. I argue that GMA became a space for publicly playing with cultural norms, political participation, and the politics of piety at some distance from the pressures that make publicly living difference so challenging.

Media Resources for “‘One Can Veil and Be a Singer!'”

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2017b. “Iran’s Daughter and Mother Iran: Googoosh and diasporic nostalgia for the Pahlavi modern.” Popular Music 36 (2):157-177.

Abstract: This article examines Googoosh, the reigning diva of Persian popular music, through an evaluation of diasporic Iranian discourse and artistic productions linking the vocalist to a feminized nation, its ‘victimisation’ in the revolution, and an attendant ‘nostalgia for the modern’ (Özyürek 2006) of pre-revolutionary Iran. Following analyses of diasporic media that project national drama and desire onto her persona, I then demonstrate how, since her departure from Iran in 2000, Googoosh has embraced her national metaphorization and produced new works that build on historical tropes linking nation, the erotic, and motherhood while capitalising on the nostalgia that surrounds her.

Media Resources for “Iran’s Daughter and Mother Iran”

DVD cover of Googoosh, Q Q Bang Bang, Taraneh Records, 2003

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2017a. “Googoosh’s Voice: An Iranian Icon in Silence and Song.” In Vamping the Stage: Female Voices of Asian Modernities, edited by Andrew Weintraub and Bart Barendregt, 234-257. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Abstract: In this chapter, I argue that Googoosh blurs the line between celebrity as exceptional individual and celebrity as medium for collective expression. In possession of a singular voice, Googoosh has presented herself as uniquely capable of reflecting voices of Iranians back to themselves. Googoosh acquired this aspect of her current persona in light of her public biography of private victimization and her postrevolutionary period of silence, and through her collaboration with an Iranian transnational public that has long concerned itself with representing alternative iterations of Iranian-ness to those promoted by the Islamic Republic (Naficy 1993, Hemmasi 2011). I trace Googoosh’s transformation from silenced to sounding female celebrity and attend to how she and her collaborators have incorporated the political metaphoric language of voice, song, and silence into her pre- and post-migration sung performances and public statements, thus drawing a correlation between her sounded vocalizations with the achievement of agentive voice. Yet, like many pop singers, Googoosh does not author her sung texts nor is she the sole creative force behind her performances, songs, or videos. I am likewise interested in how her persona “animates” (Goffman 1981) the perspectives of others through performance and media.

Media Resources for “Googoosh’s Voice”

Left: Ahmad Shamlu (source) | Right: Dariush (source)

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2013. “Intimating Dissent: Popular Song, Poetry, and Politics in Pre-Revolutionary Iran.” Ethnomusicology 57 (1):57-87.

Abstract: This article considers the oppositional role of musiqi-ye pāp vis-à-vis the pre-revolutionary Iranian state within the larger dynamics of artistic and political communication under conditions of censorship. I focus on a song called “Pariyā” (“The Fairies”), which was based on a poem by eminent Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlu (1925–2000) and later composed and recorded as a song by Dariush Eghbali, a popular pre-revolutionary musiqi-ye pāp vocalist who now lives and works between Southern California and France. The article reflects on a puzzle presented to me by Dariush and the song’s producer, music executive Manuchehr Bibiyan, who also lives and works in the Los Angeles area: although the poem “Pariyā” was published in the late 1950s, despite its poet’s known conflicts with the Pahlavi government and the poem’s oppositional undertones, the sung “Pariyā,” based on an edited version of the original poem, was banned by the state as soon as it was recorded in the early 1970s. Why, asked Dariush and Bibiyan, was “Pariyā” permitted as a poem but prohibited as a song?

Media Resources for “Intimating Dissent”

YouTube screen grab of Andy’s “Āreh, āreh” (“Yeah, yeah”), Avang Music.

Hemmasi, Farzaneh. 2011. “Iranian Popular Music in Los Angeles: A Transnational Public Beyond the Islamic State.” In Muslim Rap, Halal Soaps, and Revolutionary Theater: Artistic Developments in the Muslim World, edited by Karin Van Nieuwkerk, 85-111. Austin: University of Texas.

Chapter Abstract: Whether inside or outside the country, music plays a special role in debates about Iranian identity, engaging Iran’s relationship with Islam and the West, and raising questions regarding rights to expression, sexuality, youth, and gender, making it an ideally situated cultural form to examine in order to understand the conflicts facing the Iranian nation. Today, LA-produced music and media, and the national concerns expressed therein, are not only diasporic but transnational, reaching dispersed Iranian communities around the world as well as audiences in Iran, where they are illegal but widely consumed. As I show in this chapter, Iranian exile popular music’s homeland orientation is driven by its creators’ financial and emotional motives, but also by a desire to extend Iranian culture, identity and political expression beyond the ideological and territorial bounds of the Islamic Republic. From their positions abroad, Iranian exile popular musicians contribute to what I argue is a transnational public containing views and representations of Iranian-ness that deviate from dominant state-approved discourses. What versions of Iranian identity are explored in this music and how might these contrast with those identities and practices promoted in the Iranian revolution or by the Islamic state? Further, how effective is exile popular music in reaching widespread Iranian audiences both inside and outside of the country and how can we evaluate its influence?