Tehrangeles Dreaming: Intimacy and Imagination in Southern California’s Iranian Pop Music

Now available from Duke University Press – Use promo code SPRING50 for 50% off

“Tehrangeles,” a portmanteau combining Tehran and Los Angeles, is home to the largest concentration of Iranians outside of Iran and the birthplace of distinctive version of postrevolutionary expatriate Iranian culture. Tehrangeles pop was first created by professional musicians and media producers fleeing Iran’s revolution-era ban on “immoral” popular music. This diasporic phenomena quickly grew into a global force. Though the music is not officially allowed within Iran, and its expatriate producers rarely dare to return, Tehrangeles pop has been part of domestic daily life for decades and affords Iranian audiences an intimate experience of imaginaries from abroad. American and British governments have also incorporated Tehrangeles pop into their Iranian cultural diplomacy efforts, while the Islamic Republic has treated Tehrangeles musicians as soldiers in the “soft war” against Iran. Driven by a combination of commerce and politics, Tehrangeles pop musicians operate on the principle of “giving the Iranian people what they want”—but can’t get from officially-approved versions of Iranian culture: women’s singing voices, social dance, nostalgia for prerevolutionary Iran, and dissent aimed at Iranian leaders and policies.

Tehrangeles Dreaming is the first book to document this fascinating cultural phenomenon. The book transports readers to all-Iranian dance parties on the beach, karaoke nights in Encino’s Cabaret Tehran nightclub, and unassuming office parks where Tehrangeles music and satellite television begins. The book also introduces readers to some of Iranian Southern California’s most fascinating figures— prerevolutionary diva Googoosh; charismatic crooner-turned-activist Dariush, and brothers Shahram and Shahbal Shabpareh, Iranian dance pop pioneers. Drawing on ethnographic research in Los Angeles; musical and textual analysis; and close attention to the music, video, and television programs that contribute to this transnational Persian-language mediascape, Tehrangeles Dreaming argues that Iranian popular culture produced in Southern California exemplifies the manner in which culture, media and diaspora have combined to create practices and identifications that respond to, but are not circumscribed by, the nation-state and its political transformations.

Googoosh: Iranian pop diva in exile

Faegheh Atashin, better known as Googoosh (گوگوش), is Iran’s most famous pop diva. She was the primary female star of the Westernized “musiqi-ye pāp” style prior to the 1979 revolution, fell silent for nearly two decades after the revolution-era ban on female vocalists, and restarted her career in self-imposed North American exile in 2000. Two of my publications consider Googoosh’s exceptional biography and her extensive impact on transnational Iranian popular culture.

- “Iran’s daughter and mother Iran: Googoosh and diasporic nostalgia for the Pahlavi modern.“ Popular Music 36:2, 157-177. | Resources|

- “Googoosh’s Voice: An Iranian Icon in Silence and Song.” In Vamping the Stage: Female Voices of Asian Modernities, edited by Andrew Weintraub and Bart Barendegt (University of Hawai’i Press), 234-257. | Resources|

Dariush Eghbali: Star Vocalist and Humanitarian

Dariush Eghbali Live in Orange County (September 10, 2016). Photo Credit: Navid Studio Photography. Image Source: Dariush Eghbali’s Official Facebook Page

Dariush Eghbali (داریوش اقبالی)is the most popular male pop vocalist of his generation. Dariush began his career in prerevolutionary Iran, where he developed a reputation for singing both sad, sentimental songs and songs that expressed a subtle opposition to the political status quo. He left Iran around the time of the revolution and eventually joined the Iranian music industry in Southern California, where he reunited with many of his creative collaborators. In exile, he has been a forthright critic of the postrevolutionary Iranian government. Since 2003, his Ayeneh Foundation has addressed social maladies, especially drug addiction in Iran and diaspora, using a combination of media and direct humanitarian actions. Dariush also continues to be an extremely popular touring artist.

Dariush then and now. Left image source / Right image source.

My publications consider the effects of two of Dariush’s pre- and postrevolutionary political songs.

- “Intimating Dissent: Poetry, Popular Music, and Politics in Pre-Revolutionary Iran.” Winter 2013. Ethnomusicology 57:1, 57-87. |Resources|

-

“Rebuilding the Homeland in Poetry and Song: Simin Behbahani, Dariush Eghbali, and the Making of a Transnational National Anthem.” Popular Communication: The International Journal of Media and Culture 15:3, 192-206. |Resources|

Iranian Women’s Voices in Transnational Moral Regimes

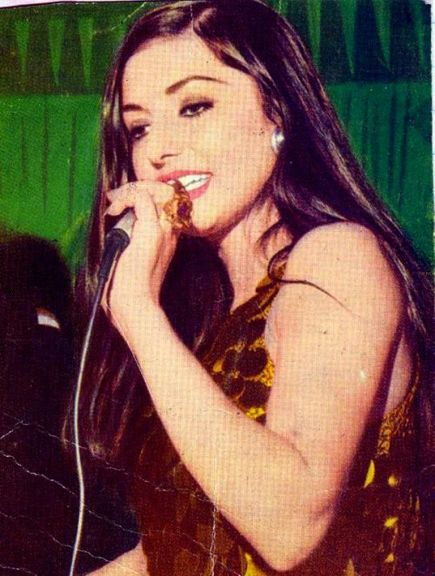

Ermia, the controversial victor of the 2013 Googoosh Music Academy reality television show. Image Source: Flickr

Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, women have been prohibited from singing solo in public because of the immoral feelings they may stimulate in unrelated male listeners (namahram). While plenty of women sing in private, a lively women’s only concert scene exists in Tehran, and women are allowed to sing in groups or as backing vocalists for male soloists, the continuing designation of the public solo female singing voice as immodest and potentially immoral imbricates women vocalists in the transnational politics of modesty and piety. The London-based Manoto1 reality television program Googoosh Music Academy brought these issues to the fore in 2013 with the participation of a veiled female contestant named Ermia (ارمیا).

- My article “‘One Can Veil and Be a Singer!’: Performing Piety on an Iranian Talent Competition,”|Resources| explores the transnational uproar that surrounded Ermia and Googoosh Music Academy in relation to the complicated postrevolutionary Iranian politics of piety, media, and diaspora.

- I discuss the broader politics of women’s singing in Iran in an interview titled “Voice and Revolution” between myself and Prof. Kevin O’Neill, Director of University of Toronto’s Centre for Diaspora and Transnational Studies.